How does one hate a country, or love one?

"How does one hate a country, or love one? ... I know people, I know towns, farms, hills and rivers and rocks, I know how the sun at sunset in autumn falls on the side of a certain plowland in the hills; but what is the sense of giving a boundary to all that, of giving it a name and ceasing to love where the name ceases to apply? What is love of one's county; is it hate of one's uncountry? Then its not a good thing. Is it simply self-love? That's a good thing, but one mustn't make a virtue of it, or a profession... Insofar as I love life, I love the hills of the Domain of Estre, but that sort of love does not have a boundary-line of hate. And beyond that, I am ignorant, I hope."

-the character Estraven from Ursula K. Le Guin's Hugo and Nebula winning novel, The Left Hand of Darkness, pg 212 (1969)

Ethical Anarchism

In the West, ethics and religion have been intertwined for centuries. We have been trained that in questions of right or wrong, good or evil, we are to look to the priests, ministers, popes and lamas for answers. While this tradition of religious-ethical combination is well entrenched in the West, it is not an inevitable pairing. For instance, in China numerous ethical philosophies, such as Confucianism, Daoism and Buddhism, mix freely with various local religious traditions (and each other) or stand alone. Even in the West we have seen the rise of non-religious ethics over the past two centuries with Ayn Rand’s Objectivism and Jeremy Bentham’s Utilitarianism being two fine examples.

Instead of equating religion and ethical philosophy as having a necessary one-to-one value (some deeply religious people can’t even fathom why an atheist would have any moral code… and then of course assume that they don’t), we should instead say that here in the West most people’s religions help define their ethical code, but that a complete ethical philosophy doe not necessarily need a religious base.

What is an ethical code without religious trappings? Ethics, at its heart, is a method for regulating our behavior with other human beings. How should we treat other people ourselves, how do we as a group inform our social decision-making and how to do we deal with those who break these regulations are the three fundamental questions of any complete ethical philosophy. In contrast, a political philosophy deals primarily with the second question (how do we make decisions as a group) and somewhat less with the third question (regulation of rule breakers); it largely ignores interpersonal relationships. It could be said that a political philosophy is either an incomplete ethical philosophy or a component of a larger ethical philosophy.

Classically, Anarchism has been considered a political philosophy, dealing with the organization of society. Yet, at the same time, as our philosophy emphasizes the importance of the individual within the group and the formation of groups in their smallest units, we have always skirted the boundaries of becoming an ethical philosophy.

I believe that it is time that we step firmly over that line and announce that Anarchism aught no longer to be considered a political alternative, but an ethical one- a system that stands on its own and will analyze morality upon its own grounds. Anarchist ethics calls for the rejection of outside standards and asks each individual human being to take the responsibility for their own moral decisions into their own hands. It asks for the universal standards of truth, beauty, freedom and love as understood by each individual to be the only ruler suitable for decision-making.

The professional moralists- the radio hosts, preachers, politicos and pundits- will of course decry the appearance of ethical anarchism, I can’t blame them since it undermines their self-appointed positions. What would happen in America if those that look to Rush Limbaugh to tell them what is right and what is wrong instead had to talk to their neighbors, co-workers and friends? If those who anxiously wait for the party politburo to release their latest statements in the party newspaper had to form their own opinions? That is the moral weight of ethical anarchism- the pressure of self-determination and the freedom of community interdependence. I quote Henry David Thoreau:

“Must the citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience, to the legislator? Why has every man a conscience, then? I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward. It is not desirable to cultivated a respect for the law, so much as for the right. The only obligation which I have a right to assume, is to do at any time what I think right… A common and natural result of an undue respect for the law is, that you may see a file of soldiers, colonel, captain, corporal, privates, powder monkeys and all, marching in admirable order over hill and dale to the wars, against their wills, aye, against their common sense and consciences” (On the Duty of Civil Disobedience, 1849)

Ethical anarchism does not ignore the questions of our earlier political philosophy; we are still interested in equitable social organization, hierarchy and oppression. What changes is that we say that since all human society emerges from the daily interaction of individuals- and the moral decisions of everyday life- any truly democratic society must emerge from those interactions. What are corporations and governments but the accumulated actions and inactions of millions? What happened if we ceased those actions and took those inactions? This is not, in the end, the question of leaders or movements, but of individual people and could, theoretically happen tomorrow. However, the dominant ethical philosophy holds that each should do his or her “duty,” and fill his or her role. The banker makes loans and takes payments, the factory worker builds chachkas, the prep-cook chops onions and each receives, in return, their daily value in green slips. To change this, except through the two acceptable political philosophies, is “unethical” and destructive to harmony and happiness. It is this ethical philosophy, underpinned by media propaganda, emotionally charged patriotism and the weight of habit, that ethical anarchism attacks at its very root. It does not seek more green slips for the cook, or the temporary victory of one political sub-philosophy, but a complete change into a more democratic, egalitarian and, in the end, ethical society.

Ind with a quote from the ever-thoughtful Weakerthans (“Ringing of Revolution”):

In a building of gold,

with riches untold,

lived the families on which the country was founded.

And the merchants of style,

With their vain velvet smiles,

Were there ‘cause they also were hounded.

And the soft middle class

Crowded in for the last

For the building was fully surrounded.

And the noise outside was the ringing of revolution.

Sadly they stared

And sank in their chairs

And searched for a comforting notion.

And the rich silver walls

Looked ready to fall

As they shook in doubtful devotion.

And the ice cubes would clink

As they freshened their drinks

With their minds in bitter emotion.

And they talked about the ringing of revolution.

And the clouds filled the room

In the darkening doom

As the crooked smoke rings were rising.

How long will it take?

How will we escape?

Someone asks but no one’s advising.

And the quivering floor

Responds to a roar

And the shake’s no longer surprising

As closer and closer come the ringing of revolution.

In tattered tuxedoes

They greet the new heroes

Who crawl about in confusion

And they sheepishly grin

For the memories within

Of the decade’s dark execution.

Hollow hands raised

They stood there amazed

In the shattering of their illusions

And the windows were smashed by the ringing of revolution.

Down on our knees

We’re begging you please

We’re sorry for the way you were driven

There’s no need to taunt

Just take what you want

And we’ll make amends if we’re living.

But a wave from the crowd

And the flames from the town

That only the dead are forgiven

And they vanished inside

The ringing of revolution.

As closer and closer come the ringing of revolution.

-by Jesse

Libertarians and Anarchists

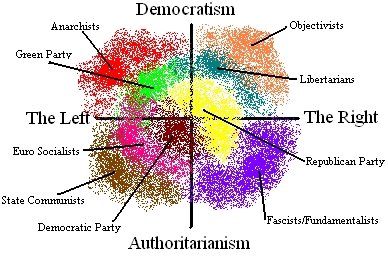

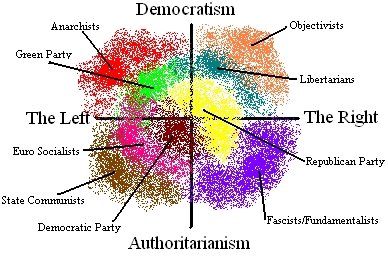

Recently, I was asked “what is the difference between a libertarian and an anarchist?” For many Americans, accustomed to thinking of politics in a “Right-Left” continuum, are confused when they are faced with two ideologies so in-line on many issues and yet so radically different. One way to begin to reconcile the differences is to visualize a political spectrum with two dimensions (like X-Y diagrams in Math class): with the Left and Right in opposition and Democratism in opposition to Authoritarianism. In a diagram drawn like this (see below), we find that Anarchists and Objectivists (followers of Ayn Rand) have as much in common as Anarchists and State Communists (who are called plain Communists in America); in the same vein, Anarchists are directly opposed to Fascists and Fundamentalists, Objectivists to State Communists and Libertarians to Eurosocialists.

So what Anarchists and Libertarians have in common is a belief in personal liberty, an emphasis on decentralization of power and a dislike of governments having control over our lives. At the same time, they are like Communists as they oppose Capitalism, the concentration of private wealth, the oppression of minority groups and consumerism.

I believe that the fundamental difference between Anarchists and their counterparts on the Right (Objectivists and Libertarians) is over private property. As best I can understand it, the Right has collapsed the idea of property rights with personal rights. Morally gained property exists as a hedge against the power of society’s dictates and protection for one’s future goals. The right to hold property, especially land, is a sacred, exclusive one; for instance, a landholder has the right to block public access, to develop as he or she chooses and to ecologically degrade the land. Money (a stand-in for other private property and a form of concentrated social power) can be spent in any way the holder sees fit, provided it does not impede on another’s right to hold property. The Right seeks “market solutions” (those involving private profit, either with private or public property) to social, economic and ecological problems.

However, to the Anarchist, property is not a right and cannot ‘belong’ to a person. There is an old saying “We do not inherent our land from our fathers, but borrow it from our children.” The land and, in one shape or another, all property, existed before the ‘owner’ was born and will exist after they die; at the most, we have a lease to property.

This also means that there is a negation of rights regarding exclusion and use. The Right holds that a person should be able to do however they see fit with what they own, but no-one disagrees that we do not have the right to shoot our neighbor in cold blood… even if we use our own gun and it occurs on our own land. Likewise, we cannot pour arsenic into our neighbor’s well… or at the top of the aquifer that feeds the well on our land. There is no set dividing line between putting a gun to another person’s head and flooding her land with cheap corn and driving her family into absolute poverty. A person’s right to use the property entrusted to them extends only as far as it does not harm other people or the community.

Anarchism does, however, recognize the right to provide for one’s loved ones, community and self through the use and creation of property. Objects of art created for their beauty, or tools for their utility are the creators’ to keep, give or trade as they desire; the act of creating the art or building the object has conveyed that right to the creator. So the factory workers own the objects they create (but with them in this ownership are those who gather the raw materials, make the design and transport the product), until such time as their use runs counter to the rights of the community at large, human and non-human. In other words, in our communities you keep your own toothbrush until you stab someone else with it.

Anarchists also reject property rights because of the effect they have on our values system. Inalienable property rights leads to fetishistic materialism, where the accumulation of objects and property is valued over the lives and livelihoods of people. Valuing profit over people is only possible in a world where the rights of property holders are held above the health and well being of others.

This does not, however, mean that the Anarchist believes in State regulation, for we view the State as primarily an oppressive organization developed for the protection of the property and privilege of the few over the many. Thus Anarchists don’t support zoning, governmental land redistribution, welfare or any other Liberal, Authoritarian projects. We abhor forced collectivization and planned economies.

A rejection of an illegitimate State’s ability to regulate our lives does not equate a rejection of a community’s ability to defend itself from threats, both internal and external. When your neighbor poisons your well, you and your community have the right to stop him, most likely by depriving him of the property he holds in trust and has misused. The deprivation of misused property, provided it does not lead to hunger or other deprivation, ought not to be morally equated with imprisonment, dismemberment or death, which are always violations of another’s human dignity.

In the end, Anarchism is not about defending my rights or my property, but standing up for our dignity and our way of life; it is about community consensus, not bureaucratic fiat and in the area of property, it values good stewardship and treating land and property as being held in trust. We are not kings of our castles, but shepherds of our children’s flocks.